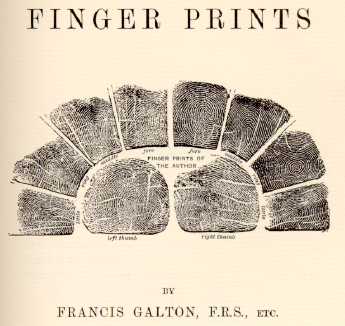

Fingerprinting

In this portion of our forensics project, we placed our fingers on a light surface and allowed the grease to from a print. We then gingerly brushed a dark powder on the print so as not to disturb the print's shape and to make it more visible to the naked eye. A piece of tape must be placed over the powder to lift the fingerprint as if at a crime scene. Lastly, the piece of tape with the newly lifted fingerprint has to be applied to a light colored piece of paper in order for further examination and analysis.

In this fingerprinting section of our forensics lab, we were each required to stamp our fingerprints in blue ink and place our prints in the corresponding box. We then identified the types of loops, arches, or whorls present in each fingerprint based on a given picture of each.

Hair/Fiber Analysis

For this lab, our groups had to analyze various samples of hairs and fibers through a microscope and identify unique traits of each. Pictured above, some of the analyzed samples were African-American hair, synthetic hair, dyed hair, nylon fabric, and cotton. Identifying traits include the color of the hair or fiber, the condition of the tip, and any oddities that make the sample easily identifiable.

Lipstick Analysis

For the lipstick analysis, we each had to apply lipstick and place a lip print on a notecard. Easily discernible features of an individual's lip include space between the lips, any scars on the lip, humps/arches, ratio of the size of the top lip to the bottom lip, chapped lips, and the general shape of the lip. As seen above in my lipstick print, I have distinct humps on my upper lip, a small space between by lips, lines running through my bottom lip, and a full bottom lip that is a lot bigger than my top. At a crime scene a lipstick print may be left behind for forensic examiners to analyze. However, the analysis of a lip print won't actually positively identify a single suspect like a fingerprint might.

Handwriting Analysis

Pictured above is one of the exercises we completed to demonstrate forensic handwriting analysis. In the first box is my writing with observations made by a forger. In the second box is a freehand forgery in both print and cursive. As clearly demonstrated, the letters in the forgery appeared very close to the original. However, the line habits are completely off as they slant steeply downward in the forgery. In addition, the ratio of the characters is a lot larger than the original, as are the spaces between the letters. In the third box is a traced forgery, which is understandably a lot more accurate than the freehand. Still, the traced forgery can be identified by the pen pressure. The forger seemed to have pushed down too hard on their pencil in an effort to replicate the original. Also, the line quality is shaky in areas where the forger tried to retrace certain letters, like the "f" in fox. In my opinion, tracing a forgery is a lot easier than freehanding. This is because in freehanding, the forger has to carefully replicate every aspect of the original writing while maintaining a steady speed to avoid shaky letters. In contrast, tracing only requires the forger to be focused on pen pressure, line quality, and simply following the shapes of the letters.

We were also required to write a fake check and tear it into pieces. People in other groups were then supposed to piece the checks back together and compare them to a stack of handwriting samples. We were all successful in my group in determining the writer of the check. The most identifying aspect of the writing was the ratio of characters, the line quality, and the distinctive shape of certain letters in both samples.

Footprint Analysis

For footprint analysis, each person in my group placed their foot in a bin of dirt to analyze details of the bottom of their shoe. The analysis of a footprint can reveal the relative weight of the person, the kind of shoe (revealed by certain patterns), and can positively identify a suspect if the print is very unique and similar to the suspect's shoe. The rarity of the designs on the bottom of the shoe can help solve a case by identifying a single suspect. In this exercise, we analyzed the weather conditions, the substance the print was left in, and important aspects of the footprint (size, writing, designs).

Drug Analysis

Drug | pH | Cocaine Reagent | LSD Reagent | Methamphetamine Reagent |

1 | 5 | + | - | - |

2 | 9 | + | - | - |

3 | 2 | - | + | - |

4 | 8 | + | - | - |

5 | 6 | + | - | - |

6 | 3 | - | + | - |

Poison

Sample | Metal Poison |

1 | Pb |

2 | Fe |

3 | none |

Sample | Sugar |

1 | No sugar present |

2 | No sugar present |

3 | No sugar present |

Sample | Odor | pH | Color after PHTH |

1 | Like cleaning products | 11 | pink (contains ammonia) |

2 | odorless | 8 | colorless |

3 | odorless | 7 | colorless |

Sample | pH | Color after BTB |

1 | 2 | yellow (contains aspirin) |

2 | 8 | blue |

3 | 7.5 | blue |

Sample | Color after Fe+3 |

1 | colorless |

2 | blood red (cyanide present) |

3 | colorless |

Sample | Color after Starch |

1 | yellow |

2 | pink |

3 | blue (iodine present) |

Facial Recognition/Witness Experiment

The witness project was a unique experiment in which we didn't focus on facts or analytical examination but rather human relation and memory. In a group of six, we each cut out similar faces in several different magazines (faces must have same color and same size, otherwise the experiment will be invalid). After the faces were cut out, we cut individual facial features out, like the eyes, nose, mouth, and ears. The whole group placed their pieces in piles according to facial features. We then each drew from the pile pieces that would make a face, not necessarily the same face we had before. The faces were passed amongst ourselves, with ten seconds to memorize everything we could about the other person's constructed face. The faces were disassembled, placed in piles like before, and drawn back out to try to reassemble the memorized face. My results in the test are shown above, and my whole group's results were 100% accurate.